Share this post:

The use of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) – previously referred to as “novel oral anticoagulants”, or NOACs, which is now a banned abbreviation because it may be confused with “no anticoagulant” – has increased considerably in recent years.1,2 DOACs account for more than 50% of all outpatient anticoagulant use.1 Current American College of Chest Physicians guidelines on management of antithrombotic therapy in venous thromboembolism (VTE) and European Society of Cardiology guidelines for management of atrial fibrillation each recommend DOACs in preference to warfarin.3,4 The 2014 joint guidelines provided by the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and Heart Rhythm Society for the management of atrial fibrillation currently do not recommend the use of DOACs over warfarin, but there is reason to believe this will change in future versions of the guidelines.5

Although DOACs offer several conveniences over warfarin, as their indications expand and additional uses are explored (i.e., acute coronary syndromes, transcatheter aortic valve replacement, and extended treatment of VTE), dosing strategies are becoming increasingly complex. Recent observational data from a registry of patients with atrial fibrillation indicated that 87% of patients on a DOAC received the appropriate dose.6 Although this is a “B+” grade, inappropriate dosing for these high-risk medications more than 10% of the time is simply unacceptable. Part 1 of this 2 part series on anticoagulation safety will focus on common medication errors involving DOACs. Part 2 will focus on ways pharmacists can help prevent medication errors with anticoagulants, particularly as it relates to anticoagulation stewardship programs.

Inappropriate Dose for Indication

Each of the four DOACs is approved for the treatment of VTE and stroke prevention in non-valvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF), but dosing varies considerably depending on the indication (TABLE 1 and 2). The most notable difference is the initial higher dose required for the treatment of VTE. Apixaban and rivaroxaban, which can be used without initial parenteral anticoagulation therapy (e.g., subcutaneous enoxaparin), should be continued at a higher dose for 7 and 21 days, respectively.7,8 Dabigatran and edoxaban are approved for the treatment of VTE only after an initial parenteral anticoagulation run-in period and neither requires higher initial doses.9,10

Dosing regimens for DOACs continue to grow in complexity. For example, low-dose rivaroxaban (i.e., 2.5 – 10 mg) has recently been studied for the extended treatment of VTE and is actively being studied for prevention of thrombosis following transcatheter aortic valve replacement and following cardiac stent placement in patients with atrial fibrillation.11 Failure to identify the indication for a DOAC renders us unable to evaluate the prescription for safety, efficacy, and appropriateness. Just as you would never blindly verify a prescription for a child without first knowing their age and/or weight, pharmacists should never verify a prescription for a DOAC without first knowing the indication.

Table 1: Approved DOAC Dosing for Treatment of VTE7-10

| Medication | Dose | Dose Adjustment for Renal Function |

| Dabigatran* | 150 mg twice daily AFTER 5 days of parenteral anticoagulation | Avoid use if CrCl < 30 ml/min |

| Rivaroxaban** | 15 mg twice daily x 21 days followed by 20 mg daily | Avoid use if CrCl < 30 ml/min |

| Apixaban** | 10 mg twice daily x 7 days followed by 5 mg twice daily | No dosage adjustment required |

| Edoxaban* | 60 mg daily AFTER 5 days of parenteral anticoagulation | 15-50 ml/min: 30 mg once daily |

*Dosing may be different with concomitant p-glycoprotein inhibitors or inducers

**Dosing may be different with concomitant p-glycoprotein and strong CYP3A4 inducers or inhibitors

Table 2: Approved DOAC Dosing for Treatment of NVAF7-10

| Medication | Dose | Dose Adjustment for Renal Function |

| Dabigatran* | 150 mg twice daily | CrCl 15-30 ml/min: 75 mg twice daily

CrCl < 15 ml/min: Avoid use |

| Rivaroxaban** | 20 mg once daily | CrCl 15-50 ml/min: 15 mg once daily

CrCl < 15 ml/min: Avoid Use |

| Apixaban** | 5 mg twice daily | If 2 of 3 criteria met (SCr >1.5 mg/dl; weight < 60 kg; age ≥ 80 years old): 2.5 mg twice daily |

| Edoxaban*‡ | 60 mg twice daily | CrCl 15-50 ml/min: 30 mg once daily

CrCl < 15 ml/min: Avoid use |

*Dosing may be different with concomitant p-glycoprotein inhibitors or inducers

**Dosing may be different with concomitant p-glycoprotein and strong CYP3A4 inducers or inhibitors

‡Contraindicated if CrCl > 95 ml/min

Inappropriate Dose for Renal Function

For DOACs, the degree of renal dysfunction that warrants dose adjustment is dependent on the DOAC, indication, drug-drug interactions, and patient-specific factors (i.e., age and weight). Important error-prone tendencies include dose adjusting based on the wrong indication, failure to account for how drug-drug interactions (DDI) affect dose adjustment cutoffs, and incorrectly estimating creatinine clearance.

It should be noted that the method used to calculate CrCl can cause significant discordance in DOAC dosing. The calculation used for estimating CrCl in clinical trials involving DOACs was the Cockroft-Gault method. Although it may be less appropriate to estimate CrCl using this method in certain patient populations (e.g., patients with acute kidney injury or morbid obesity), Cockroft-Gault should be the standard for calculating CrCl for the chronic use of these agents in clinical practice.12 Patients with an estimated CrCl < 60 ml/min and older adults are particularly at risk for dosing discordance if renal function is improperly estimated, with greater implications for rivaroxaban and dabigatran dosing than apixaban.

Key Points When Evaluating Renal Function for DOAC Prescriptions:

- Dose adjustment for renal function varies by indication

- Drug-drug interactions can impact dose adjustment criteria in patient with renal dysfunction

- Cockroft-Gault should be used for estimating renal function

Failure to Account for Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Drug Interactions

Although DOACs have significantly fewer DDI than warfarin, it is important not to forget that relevant DDI do exist and failure to acknowledge them places patients at risk for bleeding or thromboembolic events. Rivaroxaban and apixaban are metabolized by cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4) and are substrates for permeability glycoprotein (P-gp). Significant DDI occur with medications that inhibit or induce both CYP3A4 and P-gp (TABLE 3).7,8 Dabigatran and edoxaban rely less on metabolism by the liver, but do have significant DDI with P-gp inhibitors and inducers (TABLE 4).9,10

Table 3: Drug-Drug Interactions with Rivaroxaban and Apixaban13

| Mechanism of Interaction | Drug-Drug Interaction | Therapeutic Effect | Suggested Management |

| P-gp and strong CYP3A4 inducers | • Barbiturates

• Phenytoin • Carbamazepine • Rifampin • St. John’s Wort |

↓↓ rivaroxaban and apixaban concentrations | Avoid concomitant use with rivaroxaban and apixaban |

| P-gp and strong CYP3a4 inhibitors | • Clarithromycin

• Grapefruit • Itraconazole • Ritonavir |

↑↑ rivaroxaban and apixaban concentrations | Avoid concomitant administration with rivaroxaban

Dose reduce apixaban by 50%; if taking 2.5 mg bid avoid concomitant use |

| P-gp and moderate CYP3A4 inhibitors | • Dronedarone

• Diltiazem • Cyclosporine • Verapamil |

↑ rivaroxaban and apixaban concentrations | Caution in combining with rivaroxaban if CrCl < 80 ml/min

No dose adjustment with apixaban |

Table 4: Drug-Drug Interactions with Dabigatran13

| Mechanism of Interaction | Drug-Drug Interaction | Therapeutic Effect | Suggested Management | |

| P-gp Inducers | • Barbiturates

• Phenytoin |

• Carbamazepine

• Rifampin • St. John’s wort |

↓↓ dabigatran concentrations | Avoid concomitant use |

| P-gp Inhibitors | • Amiodarone

• Dronedarone • Clarithromycin • Grapefruit • Tacrolimus |

• Itraconazole

• Ritonavir • Diltiazem • Verapamil • Cyclosporine |

↑↑ dabigatran concentrations | Avoid concomitant use if CrCl < 30-50 ml/min* |

The significance of a given DDI varies substantially depending on the drug(s) involved as well as whether concomitant renal dysfunction is present. For example, although an interaction exists between diltiazem and rivaroxaban, the relevance of this interaction is variable depending on renal function. In patients with normal renal function this interaction may be of little significance; however, in a patients with a CrCl < 50 – 60 ml/min. this interaction could significantly influence serum concentrations.

It should also be noted that pharmacodynamic interactions (e.g., duplications in therapy) are common, particularly in the inpatient setting.14,15 Common errors reported in the literature include duplications in therapy with VTE prophylaxis (e.g., subcutaneous heparin ordered concomitantly with a DOAC) and failure to acknowledge other anticoagulants that may have been received but are not active orders (e.g., previously administered anticoagulants that were discontinued a short period of time before ordering a DOAC). It is imperative that a thorough profile review be conducted when inpatient pharmacists verify orders for DOACs to prevent avoidable medication errors and adverse drug events.

Recommendations for Approaching Drug-Drug Interactions with DOACs:

- Avoid strong drug-drug interactions

- Attempt to switch to a different DOAC to avoid the interaction or consider warfarin

- “Moderate” interactions should be taken on a case-by-case basis, with added precaution in those with renal impairment

Dose Adjustment Based on Clinical Gestalt

Real world data suggests that inappropriate under-dosing of DOACs occurs in up to 10% of patients with NVAF.6 Under-dosing is more likely in patients whom clinicians perceive have a heightened risk of bleeding (e.g., older adults, females, and patients with moderate renal dysfunction). It is prudent to avoid making dose adjustments based on clinical suspicion, or “gut feeling”, in patients who don’t meet dose adjustment criteria because often the perceived heightened risk of bleeding is matched, if not exceeded, by a heightened risk of thrombosis.16,17

Conclusion

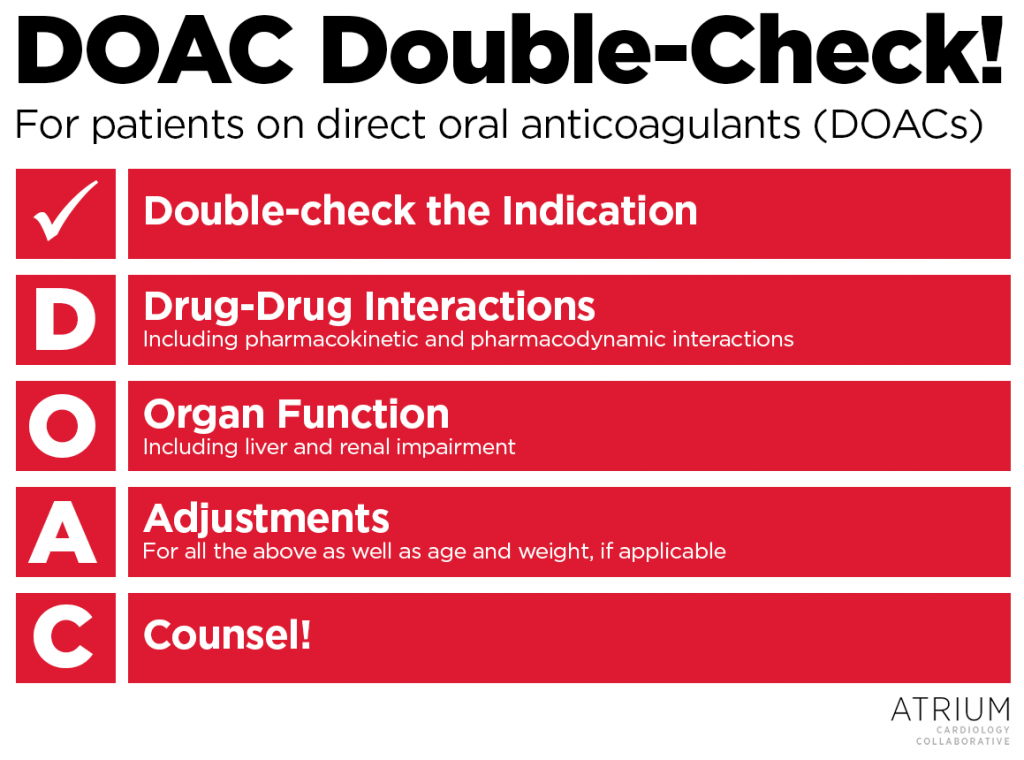

Anticoagulants, including DOACs, are some of the most commonly implicated drugs involving emergency department visits and hospitalizations due to adverse drug events.18 Medication errors can significantly influence these events, and pharmacists are at the forefront for preventing medication errors from reaching the patient. Often identifying these errors requires clinical curiosity that prompts pharmacists to ask questions, perform investigative work, and sometimes go beyond what may be required. As a reminder for pharmacists, do a D-O-A-C Double-Check! on each and every patient of yours receiving a DOAC:

- Double-check the indication – This is the only way of identifying what the appropriate dose should be!

- Drug-drug interactions – This includes pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamics interactions, such as duplications in therapy.

- Organ function – Verify whether the patient has renal or liver dysfunction. Use Cockroft-Gault for estimating renal function.

- Adjustments – Adjust the dose for any of the above as well as age and weight, if applicable, and be consistent with package label dose adjustment criteria.

- Counsel! – Counsel patients on how to take their medication and key safety considerations, and educate providers on appropriate dosing considerations.

Feel free to use our handy DOAC Double-Chek guide as an image below!

Other Resources

For additional resources on practical guidance on safely managing DOACs, see below:

- Updated European Heart Rhythm Association Practical Guide on the use of non-vitamin K antagonist anticoagulants in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Europace (2015) 17, 1467–150.

- Guidance for the Practical Management of the Direct Oral Anticoagulants in VTE Treatment. Journal of Thrombosis and Thrombolysis. (2016) 41:206.

|

Zachary R. Noel, PharmD, BCPS

|

References

- Barnes, et al. National Trends in Ambulatory Oral Anticoagulant Use. Am J Med. 2015:128, 1300-1305

- Institute for Safe Medication Practices. 2015 List of Error-Prone Abbreviations, Symbols, and Dose Designations. https://www.ismp.org/Tools/errorproneabbreviations.pdf

- Antithrombotic Therapy for VTE Disease CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. CHEST. 2016; 149(2):315-352

- 2016 ESC Guidelines for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2016.

- 2014 ACC/AHA/HRS Guideline for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation. Circulation. 2014;129:000–000.

- Off-Label Dosing of Non-Vitamin K Antagonist Oral Anticoagulants and Adverse Outcomes: The ORBIT-AF II Registry. JACC. 2016;68:2597–604

- Xarelto®. Package Insert.

- Eliquis®. Package Insert.

- Savaysa®. Package Insert.

- Pradaxa ®. Package Insert.

- ClinicalTrials.gov. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/home

- Manzano-Fernández S, et al. Comparison of estimated glomerular filtration rate equations for dosing new oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2015 Jun;68(6):497-504.

- Burnett AE, et al. Guidance for the practical management of the direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) in VTE treatment. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2016. 41:206–232

- Quarterly Watch. www.ismp.org. Accessed March 21 , 2017.

- Andreica, I. Oral Anticoagulants: A review of common errors. Pennsylvania Safety Advisory. 2015

- Alexander JH, Andersson U, Lopes RD, et al. Apixaban 5 mg twice daily and clinical outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation and advanced age, low body weight, or high creatinine. JAMA Cardiol. 2016; DOI: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.1829.

- Barra ME, Fanikos J, Connors JM, et al. Evaluation of dose-reduced direct oral anticoagulant therapy. Am J Med. 2016 Jun 21; DOI: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.05.041.

- Shehab N. US Emergency Department Visits for Outpatient Adverse Drug Events, 2013-2014. JAMA. 2016;316(20):2115-2125.

Share this post: