Share this post:

Author: Zachary R. Noel, PharmD, BCCP

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) has proven to be an effective treatment option for patients with severe aortic stenosis at intermediate-high risk for complications with surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR).1 In fact, among Medicare beneficiaries, TAVR has surpassed the number of bioprosthetic valves that are replaced surgically.2 In spite of the growing popularity of TAVR, the optimal antithrombotic regimen remains unknown.1,3 This blog outlines current guideline recommendations for post-TAVR antithrombotic therapy and gives guidance on how to handle special populations and patient-specific factors (e.g., concomitant atrial fibrillation, recent coronary artery stenting, or patients at high risk for bleeding).

What is the current standard of care for post-TAVR antithrombotic therapy?

The 2017 American Heart Association(AHA)/American College of Cardiology (ACC) Focused Update on the 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for Management of Valvular Heart Disease suggest using dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) for up to 6 months following TAVR.1 This recommendation stems from the duration studied in landmark TAVR trials.4-6 In these trials, patients were given aspirin and clopidogrel 300 mg pre-procedurally and continued on DAPT for 3-6 months post-procedure. Afterwards, aspirin or clopidogrel was continued indefinitely.

The Focused Update also gives a weak recommendation for considering anticoagulation with warfarin (goal INR 2.5) for 3 months following TAVR in patients at low risk of bleeding. This recommendation stems from observational studies showing subclinical leaflet thrombosis in up to ~20% of patients who have undergone a TAVR.7 While subclinical leaflet thrombosis infrequently leads to overt thrombosis, it has been shown to increase the rate of valve failure and transient ischemic attack (TIA).7 Of note, the guidelines acknowledge limited data with direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) following TAVR but fail to provide any recommendations on their use.

Should we empirically use anticoagulation to prevent leaflet thrombosis?

Because of the aforementioned concerns with subclinical leaflet thrombosis, many have wondered whether we should empirically use oral anticoagulation rather than antiplatelet therapy alone. While this seemed like an attractive approach, recent results from the Global Study Comparing a rivAroxaban-based Antithrombotic Strategy to an antipLatelet-based Strategy After Transcatheter aortIc vaLve rEplacement to Optimize Clinical Outcomes (GALILEO) trial have put a damper on our enthusiasm.8 The GALILEO trial compared rivaroxaban 10 mg plus aspirin 75-100 mg daily for 90 days, followed by rivaroxaban 10 mg daily, to standard of care (aspirin plus clopidogrel) in patients without an indication for anticoagulation (e.g., atrial fibrillation or treatment of venous thromboembolism). Unfortunately, the trial was stopped early for increases in all-cause death (6.8% vs 3.3%), major or life threatening bleeding (4.2% vs 2.4%), and death or thromboembolic events (11.4% vs 8.8%). The full results are yet to be published.

An ongoing study of full dose apixaban (Anti-Thrombotic Strategy After Trans-Aortic Valve Implantation for Aortic Stenosis (ATLANTIS)) is being conducted in post-TAVR patients and will include patients with atrial fibrillation.9 Results are not expected until 2020. Additionally, the Antiplatelet Therapy for Patients Undergoing Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation (POPular-TAVI) study is comparing antithrombotic strategies in patients with and without indications for oral anticoagulation. Results are not expected until 2020.10

What about patients with atrial fibrillation and/or coronary artery disease?

Atrial fibrillation and coronary artery disease are common comorbidities in patients with aortic stenosis. Upwards of 50% of patients who undergo TAVR have concomitant atrial fibrillation, or develop it shortly thereafter, and nearly 35% undergo coronary artery stenting.3 In addition, patients with severe aortic stenosis often have multiple risk factors for ischemic stroke, including hypertension, heart failure, and advanced age. Thus, prudent use of anticoagulation is necessary to reduce the risk of stroke. A consensus document published by the European Heart Rhythm Association recommends anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation, with or without a single antiplatelet agent depending on comorbidities.3 In patients with atrial fibrillation and recent acute coronary syndrome or coronary stent within 6 months, dual therapy with an anticoagulant and a single antiplatelet is recommended. Importantly, triple therapy should be avoided given the excessive bleeding risk with little to no additional thromboembolic protection. When considering dual therapy, DOACs are associated with fewer bleeding complications and similar or improved thromboembolic endpoints compared to warfarin. 11 Additionally, dual therapy with a DOAC plus a P2Y12 inhibitor has been shown to have similar efficacy with fewer bleeding complications compared to triple therapy with warfarin plus DAPT.12-13 Therefore, a DOAC plus a P2Y12 inhibitor may be a preferred option in patients with concomitant atrial fibrillation and recent acute coronary syndrome or coronary stents.

What about patients at high risk for bleeding?

Many patients undergoing TAVR have multiple risk factors for bleeding, including advanced age, renal insufficiency, and concomitant use of antiplatelet medications. Tailoring antithrombotic therapy based on individual risk factors is often warranted. Most commonly, antiplatelet therapy can be tailored and/or discontinued to reduce bleeding risk. For patients without recent acute coronary syndrome or coronary artery stenting (i.e., within the last six months) and no indication for anticoagulation, consider single antiplatelet therapy. The Aspirin Versus Aspirin + Clopidogrel Following Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation (ARTE) trial randomized patients to single (aspirin 80-100 mg/day) vs dual antiplatelet therapy (aspirin 80-100 mg plus clopidogrel 75 mg daily) in patients post-TAVR.14 The trial showed no significant difference in cardiovascular events but a significant increase in major or life threatening bleeding in those on dual therapy (3.6% vs 10.8%; p-value 0.038). While the trial was small (N=222 patients), the results are compelling, particularly for patients at greatest risk for bleeding. A recent meta-analysis corroborates these findings and begs the question whether DAPT therapy should be used at all post-TAVR, or whether aspirin monotherapy is sufficient.15

For patients with atrial fibrillation, discontinuing antiplatelet therapy is the most effective way to mitigate bleeding risk while maintaining stroke protection. This is true even in many patients with a history of coronary artery disease. Importantly, dose reducing direct oral anticoagulants outside the parameters of the package labeling in an attempt to mitigate bleeding risk has been associated with higher rates of stroke and should be avoided.16-17

Closing Thoughts

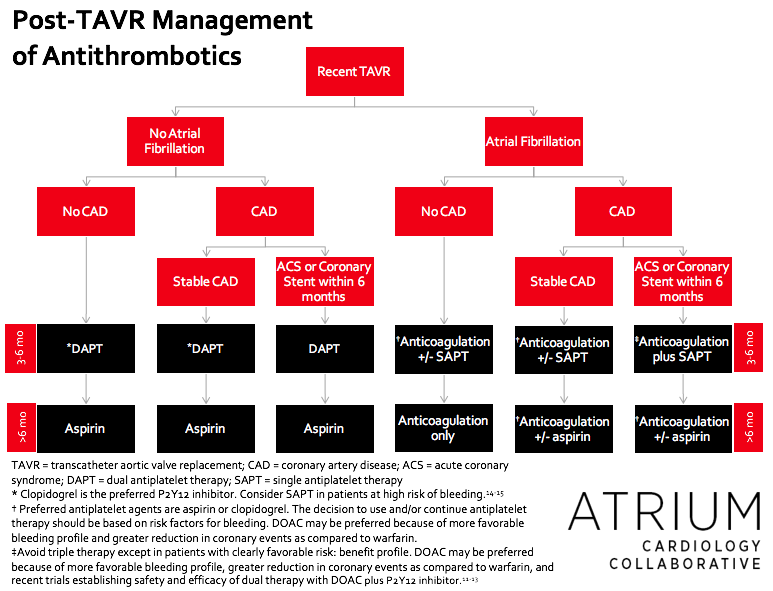

Post-TAVR antithrombotic therapy is highly variable and patient specific. It is not possible to have a “one size fits all” approach. The most important patient-specific considerations include history of atrial fibrillation, recent acute coronary syndrome or coronary stent, and risk factors for bleeding (e.g., history of bleeding event, age, renal function, concomitant medications). Figure 1 provides general guidance on how to approach these main patient-specific considerations.

|

Zachary R. Noel, PharmD, BCCP

|

References

- Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline: Focused Update: 2017 AHA/ACC Focused Update of the 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease. A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2017;70:252-289. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.03.011.

- Culler SD, Cohen DJ, Brown PP, et al. Trends in Aortic Valve Replacement Procedures Between 2009 and 2015: Has Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement Made a Difference? The Annals Of Thoracic Surgery. 2018;105(4):1137-1143. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2017.10.057.

- Lip GYH, Collet JP, Caterina R de, et al. Antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation associated with valvular heart disease: a joint consensus document from the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) and European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Thrombosis, endorsed by the ESC Working Group on Valvular Heart Disease, Cardiac Arrhythmia Society of Southern Africa (CASSA), Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), South African Heart (SA Heart) Association and Sociedad Latinoamericana de Estimulación Cardíaca y Electrofisiología (SOLEACE). Europace: European Pacing, Arrhythmias, And Cardiac Electrophysiology: Journal Of The Working Groups On Cardiac Pacing, Arrhythmias, And Cardiac Cellular Electrophysiology Of The European Society Of Cardiology. 2017;19(11):1757-1758. doi:10.1093/europace/eux240.

- Smith CR, Leon MB, Mack MJ, et al. Transcatheter versus surgical aortic-valve replacement in high-risk patients. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;364(23):2187-2198. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1103510.

- Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack MJ, et al. Transcatheter or Surgical Aortic-Valve Replacement in Intermediate-Risk Patients. The New England Journal Of Medicine. 2016;374(17):1609-1620. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1514616.

- Reardon MJ, Van Mieghem NM, Popma JJ, et al. Surgical or Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Replacement in Intermediate-Risk Patients. The New England Journal Of Medicine. 2017;376(14):1321-1331. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1700456.

- Chakravarty T, Søndergaard L, Friedman J, et al. Subclinical leaflet thrombosis in surgical and transcatheter bioprosthetic aortic valves: an observational study. Lancet (London, England). 2017;389(10087):2383-2392. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30757-2.

- Dear Healthcare Professional. Rivaroxaban (Xarelto): Increase in all-cause mortality, thromboembolic and bleeding events in patients after transcatheter aortic valve replacement in a prematurely stopped clinical trial. October 3 2018. http://www.hpra.ie/docs/default-source/default-document-library/important-safety-information—xarelto-(rivaroxaban)-(oct-2018).pdf?sfvrsn=0

- Anti-Thrombotic Strategy After Trans-Aortic Valve Implantation for Aortic Stenosis (ATLANTIS). Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02664649?term=apixaban+tavr&rank=1. NLM identifier: NCT02664649. Accessed December 12, 2018.

- Antiplatelet Therapy for Patients Undergoing Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation (POPular-TAVI). Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02247128. NLM Identifier: NCT02247128. Accessed December 12, 2018.

- Lee CJ-Y, Gerds TA, Carlson N, et al. Risk of Myocardial Infarction in Anticoagulated Patients With Atrial Fibrillation. Journal of the American College of Cardiology (JACC). 2018;72(1):17-26. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.04.036.

- Dekkers T, Lafeber M, Kramers C. Dual Antithrombotic Therapy with Dabigatran after PCI in Atrial Fibrillation. The New England Journal Of Medicine. 2018;378(5):484-485. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1715183.

- Gibson CM, Mehran R, Bode C, et al. Prevention of Bleeding in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation Undergoing PCI. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;375(25):2423-2434. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1611594.

- Piayda K, Mohring A, Dannenberg L, et al. Aspirin Versus Aspirin Plus Clopidogrel as Antithrombotic Treatment Following Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement With a Balloon-Expandable Valve. JACC Cardiovascular Interventions. 2017;10(15):1598-1599. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2017.05.060.

- Ahmad Y, Demir O, Rajkumar C, et al. Optimal antiplatelet strategy after transcatheter aortic valve implantation: a meta-analysis. Open Heart. 2018;5(1):e000748. doi:10.1136/openhrt-2017-000748.

- Steinber BA, et al. Off-Label Dosing of Non-Vitamin K Antagonist Oral Anticoagulants and Adverse Outcomes: The ORBIT-AF II Registry. JACC. 2016;68:2597–604

- Yao X, Shah ND, Sangaralingham LR, Gersh BJ, Noseworthy PA. Non-Vitamin K Antagonist Oral Anticoagulant Dosing in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation and Renal Dysfunction. Journal Of The American College Of Cardiology. 2017;69(23):2779-2790. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.03.600.

Share this post: