Share this post:

Author: Stormi Gale, PharmD, BCCP

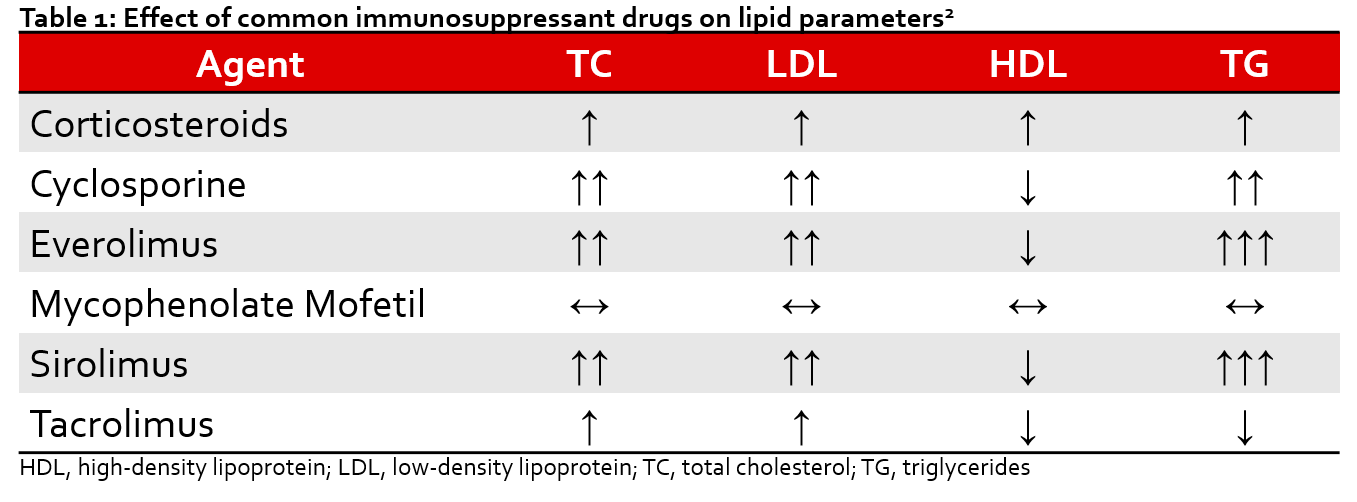

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in patients who have undergone solid organ transplantation. Dyslipidemia has an estimated prevalence of approximately 80% of this population. In the transplant population, the risk of CVD is doubled in those with total cholesterol > 200 mg/dL or triglycerides (TG) > 350 mg/dL.1 This is particularly concerning in this population considering several immunosuppressive drugs are known to induce/exercerbate abnormal lipid profiles (Table 1).2 Guidelines often neglect to specifically address these patients, leaving uncertainty around optimal management of dyslipidemia post-transplantation.

The most recent American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) Multisociety guideline recommends utilizing 10-year atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk to determine the initiation/intensity of statin therapy in the general population.3 However, the transplant population is not specifically addressed in this guideline, and there is an abundance of evidence that suggests traditional risk-scoring systems may underestimate CV risks post-transplant. Additionally, despite transplant specifically listed, factors noted by the most recent ACC/AHA guideline which enhance ASCVD risk(e.g., elevated CRP) are often observed in patients post-transplant.

Interestingly, the National Kidney Foundation Kidney Disease Quality Outcomes Initiative guidelines have considered renal transplantation to be a coronary heart disease equivalent, and as such has suggested that this population be included in the highest ASCVD risk group (in which high-intensity statin therapy would be indicated).4,5 The greatest evidence for the use of statins in kidney transplantation comes from the Assessment of LEscol in Renal Transplantation (ALERT) study, which randomized 2102 renal transplant recipients, at least 30 years of age, to either fluvastatin 40 mg daily or placebo.6 Although the study did not meet its primary endpoint of major adverse cardiac events (MACE), there was a reduction in cardiac death or nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI) in the fluvastatin group (hazard ratio (HR) 0.65 [0.48-0.88] p=0.005). Additionally, a follow-up extension suggested that fluvastatin did reduce the original primary outcome by 21% after 6.7 years, with the greatest benefit occurring in patients initiated on statin therapy within 2 years of transplantation.8 Following the publication of the ALERT study, Kidney disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) began recommending statins in all kidney transplant recipients, regardless of baseline low-density lipoprotein (LDL) level.9 These guidelnes do not specifically designate intensity, although retrospective studies have shown a dose-dependent redction in mortality with statin in patients both pre- and post-kidney transplant.10

The benefits of statins in cardiac and lung recipients has also been established. In lung recipients, statins are recommended to reduce the risk of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS), rejection, and mortality.11 Pooled data has demonstrated a reduction in cardiac allograft vasculopathy (CAV), rejection, malignancy, and improved survival in cardiac transplantation.12 Despite the known benefits of statin therapy in these patients, it is still unclear whether the intensity of statin therapy affects the magnitude of their observed pleiotropic effects, and what the role of targeting specific LDL goals might be. Some centers reserve high intensity statins for CAV or refractory dyslipidemia, although the impact of this practice remains uncertain. Nonetheless, retrospective analyses suggest that high-dose stain therapy is safe and efficacious (for LDL lowering) in heart transplant recipients receiving tacrolimus, and that targeting LDL goals less than 100 mg/dL may improve the incidence of CAV.13 More studies are needed to identify the ideal LDL goals in the post-transplant population.

The use of statins in liver transplantation presents a unique challenge due to concerns for elevations in liver transaminases. However, statins are recommended by American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases in adult liver transplant recipients in whom a LDL > 100 mg/dL can not be controlled with diet and lifestyle changes.14 Recent data further supports this recommendation asthese agents are safe and may be associated with decreased rejection and recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma.15 Larger prospective studies are needed to elicit the full benefits of statins in this population.

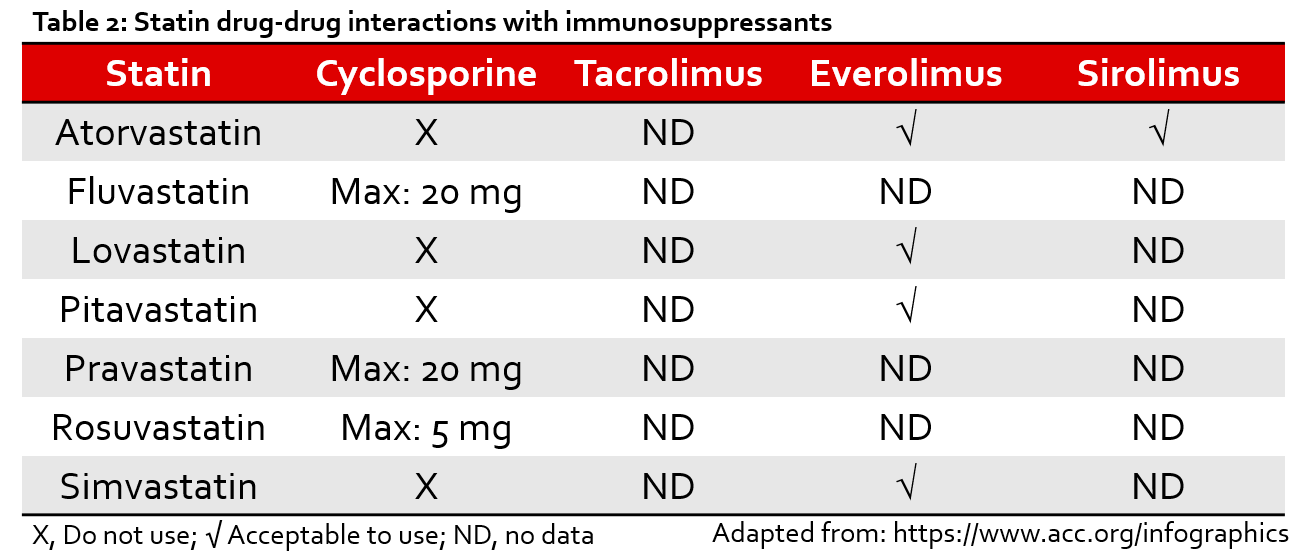

Although there is little information published regarding the prescribing of statins in transplant recipients, these agents are often underutilized in other populations due to concerns for intolerance, drug-drug-interactions (DDIs), and polypharmacy (Table 2).16,17 Because these issues are arguably even more pronounced after transplantation, it is reasonable to suspect that there is room for optimization of these agents in this population as well. Pharmacists can play an important role in identifying and intervening on potential barriers to statin use in transplant recipients.

Non-Statin Therapies

Ezetimibe is currently recommended as preferred second line therapy by ACC/AHA in patients with residual cardiac risk or who are not meeting LDL goals on maximally tolerated statins. This agent has been shown to reduce MACE when added to statin therapy in certain non-transplant populations.18 Initial concerns regarding interactions between immunosuppression (i.e., cyclosporine) and ezetimibe have been assuaged by several studies that have demonstrated safety and efficacy with coadministration of these agents, and are even recommended by the AASLD as an option in liver transplant-recipients.14,19,20

Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors are recommended in the general population for patients determined to be at very high-risk for cardiovascular disease who are already on maximally tolerated statins and ezetimibe.3 Although these agents have been shown to improve CV outcomes in high-risk populations, there is limited evidence for this class in the transplant population.21,22 However, small retrospective reports indicate that these agents may be safe and effective for LDL-lowering in patients with intolerances to or hypercholesterolemia despite statin therapy.23,24 The effect of PCSK9 inhibitors on CAV and other CV/transplant outcomes remains unclear.

Treatment of hypertriglyceridemia in the post-transplant patient is similar to that of the general population, in which statin therapy should be emphasized unless TG ≥500 mg/dL.3 The role of icosapent ethyl in this population has yet to be determined.

There is a limited role for bile acid sequestrants, fibric acid derivatives, and nicotinic acid in the post-transplant population as these agents have not been shown to improve CV outcomes in the general population and also contain concerns for additional DDIs (particularly with immunosuppression) and adverse effects.25,26

Bottom Line

The optimal management of dyslipidemia after solid organ transplantation is limited by low quality evidence and vague or nonexistent guideline recommendations. However, dyslipidemia in the post-transplant patient is prevalent and has been associated with worse outcomes. Statins encompass the greatest evidence post-transplant and should be considered in all transplant recipients. Further evidence is needed to evaluate the role of newer agents (i.e., PCSK9 inhibitors, icosapent ethyl), LDL goals, and differences in statin intensity in this population. Although statins are recommended in most tansplant recipeints, the decision regarding specific lipid-lowering regimens (e.g., statin intensity, non-statin therapy, etc.) should be based on an evaluation of the patient’s ASCVD risk and any pertinent DDIs. Each patient’s ASCVD risk and lipid profile should be assessed annually. As always, the decision on when and how to treat should be a shared-decision making process with the patient.

|

Stormi Gale, PharmD, BCCP

|

References:

- Agarwal A, Prasad GVR. Post-transplant dyslipidemia: Mechanisms, diagnosis and management. World Journal of Transplantation. 2016;6(1):125.

- Badiou S, Cristol J-P, Mourad G. Dyslipidemia following kidney transplantation: Diagnosis and treatment. Curr Diab Rep. 2009;9(4):305-311.

- Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. November 2018:25708.

- Kasiske BL, Zeier MG, Chapman JR, et al. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the care of kidney transplant recipients: a summary. Kidney international. 2010;77(4):299–311.

- Sarnak MJ, Bloom R, Muntner P, et al. KDOQI US Commentary on the 2013 KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for Lipid Management in CKD. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2015;65(3):354-366.

- Holdaas H, Fellström B, Jardine AG, et al. Effect of fluvastatin on cardiac outcomes in renal transplant recipients: a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet. 2003;361(9374):2024-2031.

- Effect of fluvastatin on cardiac outcomes in renal transplant recipients: a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. – PubMed – NCBI.

- Holdaas H, Fellström B, Cole E, et al. Long-term Cardiac Outcomes in Renal Transplant Recipients Receiving Fluvastatin: The ALERT Extension Study. American Journal of Transplantation. 2005;5(12):2929-2936.

- Wanner C, Tonelli M, Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes Lipid Guideline Development Work Group Members. KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for Lipid Management in CKD: summary of recommendation statements and clinical approach to the patient. Kidney Int. 2014;85(6):1303-1309.

- Agdamag Arianne Clare, Co Michael Lawrenz, Co Mita Zahra, Hertl Martin, Mohamedali Burhan. Abstract 19990: High Intensity Statin Improves Survival in Kidney Transplant Patients. Circulation. 2017;136(suppl_1):A19990-A19990.

- Raphael J, Collins SR, Wang X-Q, et al. Perioperative statin use is associated with decreased incidence of primary graft dysfunction after lung transplantation. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. 2017;36(9):948-956.

- Vallakati A, Reddy S, Dunlap ME, Taylor DO. Impact of Statin Use After Heart Transplantation: A Meta-Analysis. Circ Heart Fail. 2016;9(10).

- Harris J, Teuteberg J, Shullo M. Optimal low-density lipoprotein concentration for cardiac allograft vasculopathy prevention. Clinical Transplantation. 2018;32(5):e13248.

- Lucey MR. Long-Term Management of the Successful Adult Liver Transplant: 2012 Practice Guideline by AASLD and the American Society of Transplantation. 2012:140.

- Martin JE, Cavanaugh TM, Trumbull L, et al. Incidence of adverse events with HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors in liver transplant patients. Clinical Transplantation. 2008;22(1):113-119.

- Faggioni M, Baber U, Sayseng S, et al. Underutilization of High Intensity Statins in a Contemporary High Risk Pci Population. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;69(11 Supplement):1352.

- Musich S, Wang SS, Schwebke K, Slindee L, Waters E, Yeh CS. Underutilization of Statin Therapy for Secondary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease Among Older Adults. Population Health Management. 2018;22(1):74-82.

- Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, et al. Ezetimibe Added to Statin Therapy after Acute Coronary Syndromes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;372(25):2387-2397.

- Baigent C, Landray MJ, Reith C, et al. The effects of lowering LDL cholesterol with simvastatin plus ezetimibe in patients with chronic kidney disease (Study of Heart and Renal Protection): a randomised placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet. 2011;377(9784):2181-2192.

- López V, Gutiérrez C, Gutiérrez E, et al. Treatment With Ezetimibe in Kidney Transplant Recipients With Uncontrolled Dyslipidemia. Transplantation Proceedings. 2008;40(9):2925-2926.

- Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Keech AC, et al. Evolocumab and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Cardiovascular Disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(18):1713-1722.

- Schwartz GG, Steg PG, Szarek M, et al. Alirocumab and Cardiovascular Outcomes after Acute Coronary Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(22):2097-2107.

- Kühl M, Binner C, Jozwiak J, et al. Treatment of hypercholesterolaemia with PCSK9 inhibitors in patients after cardiac transplantation. Feng Y-M, ed. PLOS ONE. 2019;14(1):e0210373.

- Moayedi Y, Kozuszko S, Knowles JW, et al. Safety and Efficacy of PCSK9 Inhibitors After Heart Transplantation. Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 2019;35(1):104.e1-104.e3.

- Effects of Combination Lipid Therapy in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(17):1563-1574.

- The HPS2-THRIVE Collaborative Group. Effects of Extended-Release Niacin with Laropiprant in High-Risk Patients. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(3):203-212.

Share this post: