Share this post:

Author: Brent N. Reed, PharmD, BCCP, FCCP

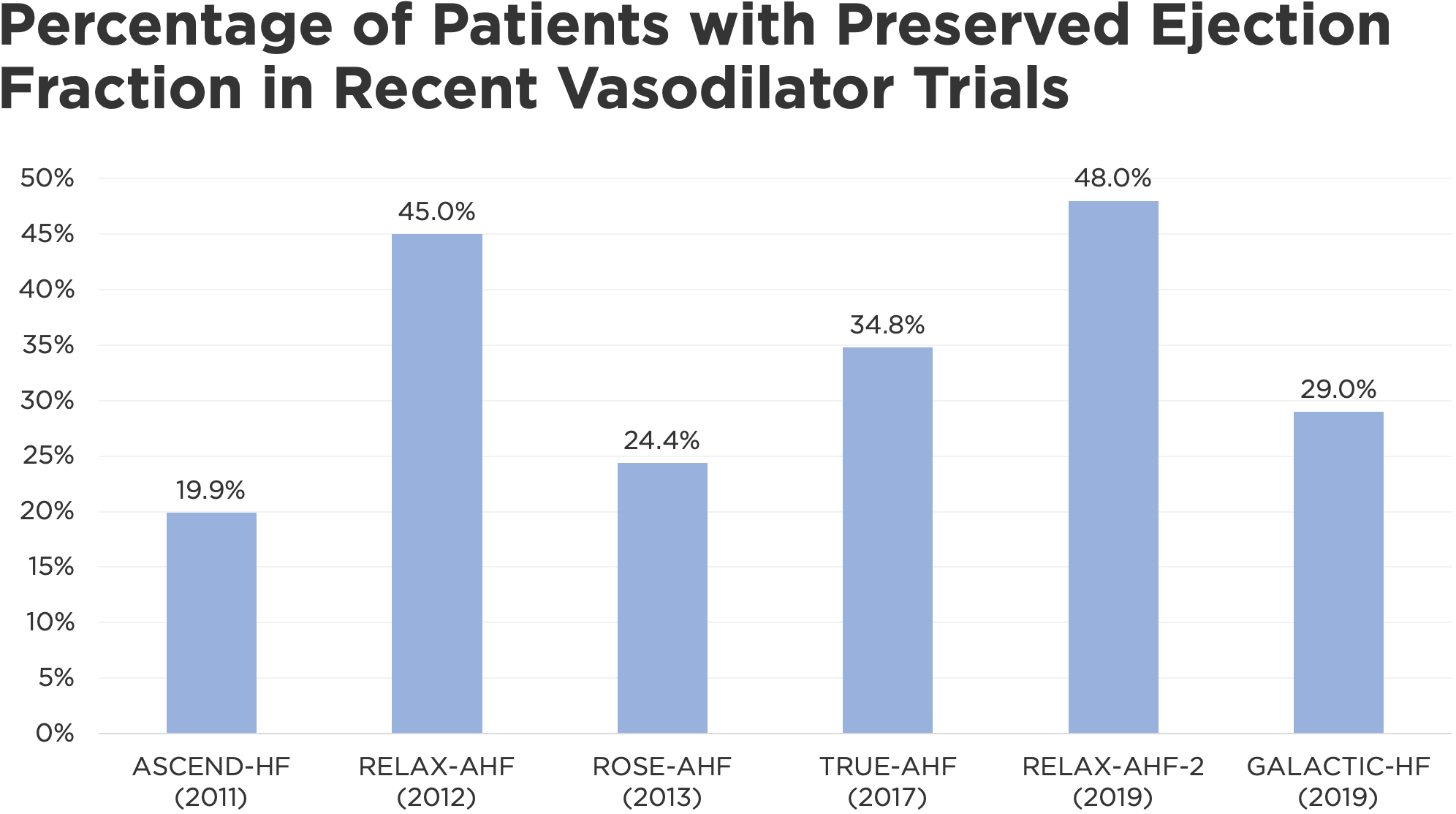

A couple of years ago, I wrote a post on how the potential benefits of vasodilator therapy in acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF) may have been obscured by the heterogeneity of patients enrolled in clinical trials. More specifically, studies have included a considerable number of patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), a population in whom acute reductions in preload and afterload may be detrimental.1 Consequently, these effects may conceal a potential benefit in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). In the time since my previous post, two additional randomized controlled trials have evaluated the early use of vasodilators in patients with ADHF and neither showed benefit.2,3 Despite signals that patients with HFpEF and HFrEF may respond differently during an acute hospitalization, both trials seem to have repeated the same mistake as their predecessors (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Recent trials assessing the use of vasodilators in acute decompensated heart failure have enrolled considerable numbers of patients with preserved ejection fraction.

Figure 1. Recent trials assessing the use of vasodilators in acute decompensated heart failure have enrolled considerable numbers of patients with preserved ejection fraction.

The first major trial to be published since my last post on this topic was RELAX-AHF 2, which compared a 48-hour infusion of the vasodilator serelaxin to placebo in 6545 patients with ADHF.2 In an earlier trial, serelaxin improved some but not all measures of dyspnea but curiously appeared to improve survival at 180 days.4 Unfortunately, the appropriately powered RELAX-AHF 2 failed to confirm this latter hypothesis. However, as I alluded to above, nearly half of the patients in RELAX-AHF 2 had underlying HFpEF (Figure 1), a subgroup in whom the benefits of acute vasodilation are less clear. Although a subgroup analysis of ejection fraction was performed as part of the overall investigation, event rates were too small to detect any meaningful trends. As a result, it is uncertain whether RELAX-AHF 2 represents a failure of the drug, the study population, or a composite of both.

The second recent trial to assess a vasodilator strategy in patients with ADHF was GALACTIC, which differed from many of its predecessors in that investigators randomized patients to a vasodilator protocol (n=386) or usual care (n=402) rather than a single agent at a fixed dose and duration compared to placebo.3 Patients in the vasodilator group initially received a combination of transdermal nitrates and low-dose hydralazine before being transitioned to an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor, angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB), or angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI). The latter therapies were titrated to target doses unless precluded by hypotension or other adverse effects.

Similar to RELAX-AHF 2, vasodilator therapy in GALACTIC failed to reduce the primary endpoint of all-cause mortality or heart failure rehospitalization at 180 days, and it did not appear to have an effect on any key secondary endpoints, such as dyspnea symptoms or length of stay. However, as with a number of recent trials in patients with ADHF, nearly one-third of those enrolled in GALACTIC had HFpEF (Figure 1). A subgroup analysis of ejection fraction was also performed as part of the overall plan in GALACTIC, but it did not yield any meaningful differences. Upon visual inspection of the forest plot, a trend appears to emerge among those with an ejection fraction < 40%, but the groups were not large enough to detect a statistically significant relationship.

In addition to the previously discussed problems associated with enrolling such a heterogeneous patient population, including those with underlying HFpEF in GALACTIC is particularly perplexing given the study’s strategy of transitioning to an ACE inhibitor, ARB, or ARNI and up-titrating to “target doses,” a term that is typically reserved for the use of these therapies in patients with HFrEF. Although renin-angiotensin-aldosterone inhibitors are commonly used in patients with chronic HFpEF, their benefits have been limited to a small reduction in hospitalizations and even those effects are inconsistent.5,6 It is therefore unsurprising that a short-term intervention would improve the composite of survival and heart failure rehospitalization at 180 days when even years of therapy have failed to improve these same outcomes in patients with chronic HFpEF.

Although these trials portend a grim future for the use of vasodilators in ADHF, there was at least one glimmer of hope in a small trial evaluating the initiation of ARNI therapy in patients with ADHF and low cardiac output (n=21).7 Similar to the GALACTIC trial, most patients were transitioned to an ARNI from other vasodilators (sodium nitroprusside in 75%) or a combination of inotropes and vasodilators (19%). Of these, ARNI was continued in 16 patients (76%) at discharge and 15 remained on therapy at 30 days. Although the study was not powered to detect improvements in long-term outcomes, the benefits of long-term ARNI therapy have been well-demonstrated previously, thus this trial primarily adds to what is known about its short-term safety.8

Bottom line: In the time since we last addressed this topic, two additional trials have appeared to question the benefit of vasodilators in ADHF. However, as with the trials before them, the heterogeneity of patients enrolled (specifically the high number of patients with HFpEF) make it difficult to discern whether the results represent a failure of drug therapy or a poorly defined patient population. Although it is unclear whether vasodilators are beneficial in a broad population of patients with ADHF and in the subgroup of patients with HFpEF, their use in patients with HFrEF is associated with improvements in hemodynamics and dyspnea relief. More importantly, the use of vasodilators may increase the proportion of patients with HFrEF who get discharged on optimal guideline-directed medical therapy.7,9

|

Brent N. Reed, PharmD, BCCP, FAHADr. Reed is an associate professor in the Department of Pharmacy Practice and Science at the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy, and practices as a clinical pharmacy specialist in advanced heart failure at the University of Maryland Medical Center in Baltimore, MD. Follow him on his website or on Twitter @brentnreed. |

Reviewed by: Stormi Gale, PharmD, BCCP

References

- Schwartzenberg S, Redfield MM, From AM, Sorajja P, Nishimura RA, Borlaug BA. Effects of vasodilation in heart failure with preserved or reduced ejection fraction implications of distinct pathophysiologies on response to therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012 Jan 31;59(5):442–51.

- Metra M, Teerlink JR, Cotter G, Davison BA, Felker GM, Filippatos G, et al. Effects of Serelaxin in Patients with Acute Heart Failure. N Engl J Med. 2019 22;381(8):716–26.

- Kozhuharov N, Goudev A, Flores D, Maeder MT, Walter J, Shrestha S, et al. Effect of a Strategy of Comprehensive Vasodilation vs Usual Care on Mortality and Heart Failure Rehospitalization Among Patients With Acute Heart Failure: The GALACTIC Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2019 17;322(23):2292–302.

- Teerlink JR, Cotter G, Davison BA, Felker GM, Filippatos G, Greenberg BH, et al. Serelaxin, recombinant human relaxin-2, for treatment of acute heart failure (RELAX-AHF): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2013 Jan 5;381(9860):29–39.

- Massie BM, Carson PE, McMurray JJ, Komajda M, McKelvie R, Zile MR, et al. Irbesartan in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2008 Dec 4;359(23):2456–67.

- Yusuf S, Pfeffer MA, Swedberg K, Granger CB, Held P, McMurray JJ, et al. Effects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and preserved left-ventricular ejection fraction: the CHARM-Preserved Trial. The Lancet. 2003 Sep;362(9386):777–81.

- Martyn T, Faulkenberg KD, Yaranov DM, Albert CL, Hutchinson C, Menon V, et al. Initiation of Angiotensin Receptor-Neprilysin Inhibitor in Heart Failure With Low Cardiac Output. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019 Oct 28;74(18):2326–7.

- McMurray JJV, Packer M, Desai AS, Gong J, Lefkowitz MP, Rizkala AR, et al. Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2014 Sep 11;371(11):993–1004.

- Mullens W, Abrahams Z, Francis GS, Skouri HN, Starling RC, Young JB, et al. Sodium nitroprusside for advanced low-output heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008 Jul 15;52(3):200–7.

Share this post: