Share this post:

Author: Kashelle Lockman, PharmD, MA

Dr. Lockman is a clinical assistant professor at the University of Iowa College of Pharmacy and an alumna of the University of Maryland Residency and Fellowship program. She can be reached on twitter at @kashellel.

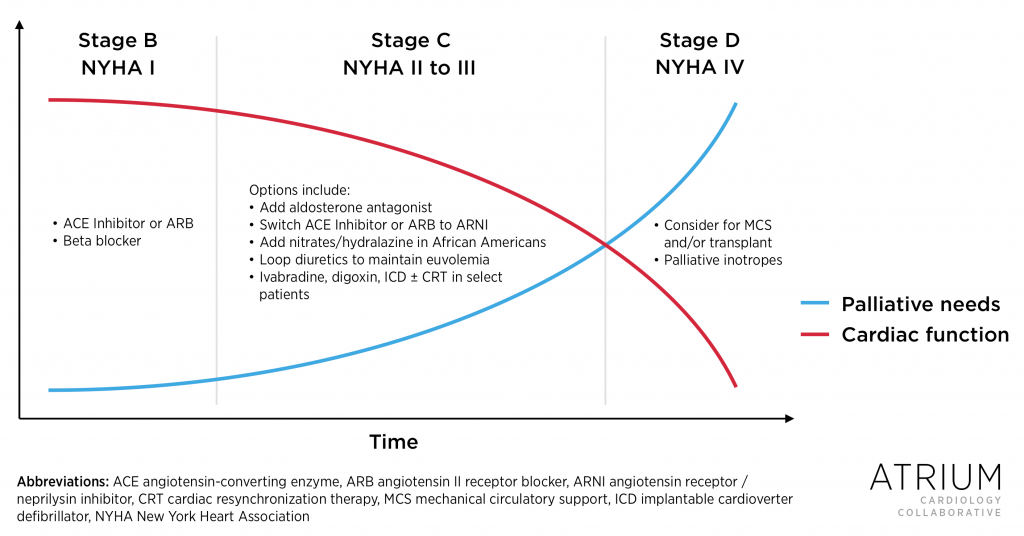

The symptom burden for patients with heart failure is equal and sometimes greater than those living with cancer, and the spectrum of symptoms may include dyspnea, pain, depression, and spiritual distress.1,2 Palliative care is a specialized interdisciplinary model of medical care that focuses on the physical, psychological, social, and spiritual dimensions of living with serious or advanced illness, and it is recommended in the 2013 American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Guidelines for the Management of Heart Failure and the 2012 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure.3-5 Due to the growing symptom burden across the trajectory of heart failure, it is essential that cardiology specialists be palliative care generalists. Conversely, palliative care specialists should be cardiology generalists (See Figure).

Figure. Decline in Cardiac Function and Palliative Care Needs (click to enlarge).

Optimal medical management is the foundation for improving symptoms in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). This often means continuing treatment with angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), beta blockers, and aldosterone antagonists, as tolerated, even when prognosis is poor and the potential mortality benefit has already been achieved. This often includes continuing these medications even when a patient enrolls in hospice care. Although these life-prolonging medications improve heart failure symptoms, what about the recently approved angiotensin receptor blocker/neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI) combination sacubitril/valsartan?

In the PARADIGM-HF trial, patients receiving sacubitril/valsartan for a mean of 8 months had less of a decline in the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) score, a 100-point assessment tool where higher scores represent lower symptom burden; patients receiving sacubitril/valsartan experienced a -2.99 point decline whereas those receiving enalapril experienced a -4.63 point decline (p < 0.001).6 However, this difference is unlikely to be of clinical significance, as prior studies have found that decreases of up to 5.3 points on the KCCQ represent only minor deterioration and not a change in New York Heart Association (NYHA) class.7

Baseline KCCQ scores for patients in PARADIGM-HF are not available, but most patients enrolled in the trial had NYHA Class II HFrEF (71%), whereas only 24% and 0.71% had NYHA class III and IV HFrEF, respectively. When subgroups were compared for the primary endpoint of cardiovascular death and heart failure hospitalizations, differences were observed in patients with NYHA class I and II HFrEF, but not in those with class III and IV disease. However, this could have been due to the enrollment of fewer patients with advanced symptoms. Similarly, no difference was observed in patients aged 75 years or greater, although they made up only a small percentage of the study population.

The 2016 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/Heart Failure Society of America Focused Update on New Pharmacological Therapy for Heart Failure recommends replacing ACE inhibitors or ARBs with combination ARNI in patients with NYHA class II-III HFrEF to reduce hospitalizations and improve mortality, and the 2016 ESC Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure recommend replacing an ACE inhibitor with an ARNI if patients remain symptomatic despite optimal treatment with an ACE inhibitor, beta blocker, and aldosterone antagonist.8,9 Based on existing data, we would anticipate that patients less than 75 years of age with NYHA class II HFrEF would experience improved quality of life with sacubitril/valsartan since it decreases hospitalizations in this population. However, for patients with NYHA class III-IV HFrEF, spironolactone or eplerenone should be considered first, as the ESC guidelines suggest. After all, the RALES trial demonstrated in a mostly NYHA class III-IV population that spironolactone confers improvements in both mortality and NYHA functional class, a symptom-based scale.

The decision to initiate sacubitril/valsartan in patients with advanced heart failure should also take prognosis into consideration, given that the time-to-benefit for individual endpoints in PARADIGM-HF was greater than 6 months. It is also important to keep in mind the age of the patient and risk for orthostasis, given that the latter was the most common adverse effect observed in PARADIGM-HF. Hopefully, future studies will clarify the mortality and symptom-related benefits of sacubitril/valsartan in early versus advanced heart failure as well is its potential as a palliative strategy.

Bottom line, based on the existing data (as of August 2016):

- In patients with NYHA Class II HFrEF, sacubitril/valsartan may be used as an alternative to an ACE inhibitor or ARB to decrease morbidity and mortality.

- In patients with NYHA Class III-IV HFrEF, consider the addition of an aldosterone antagonist to an ACE inhibitor/ARB and beta blocker, as tolerated.

- In patients with advanced heart failure and likely hospice eligibility in less than 6 months, continue ACE inhibitors or ARBs, beta blockers, and aldosterone antagonists, until more data with ARNI therapy becomes available.

References

- Bekelman DB, Rumsfeld JS, Havranek EP, et al. Symptom burden, depression, and spiritual well-being: a comparison of heart failure and advanced cancer patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(5):592-598. doi:10.1007/s11606-009-0931-y.

- Xu J, Nolan MT, Heinze K, et al. Symptom frequency, severity, and quality of life among persons with three disease trajectories: cancer, ALS, and CHF. Appl Nurs Res. 2015;28(4):311-315. doi:10.1016/j.apnr.2015.03.005.

- McIlvennan CK, Allen LA. Palliative care in patients with heart failure. BMJ. 2016;353(apr14_8):i1010. doi:10.1136/bmj.i1010.

- Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(16):1495-1539. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.020

- McMurray JJV, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, et al. ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012. European Heart Journal 2012;33:1787-1847. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs104

- McMurray JJ V, Packer M, Desai AS, et al. Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(11):993-1004. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1409077.

- Spertus J, Peterson E, Conard MW, et al. Monitoring clinical changes in patients with heart failure: a comparison of methods. Am Heart J. 2005;150(4):707-715. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2004.12.010.

- Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al 2016 ACC/AHA/HFSA Focused Update on New Pharmacological Therapy for Heart Failure: An Update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure. Circulation. 2016;CIR.0000000000000435, published online before print May 20, 2016 http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000435

- Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, et al.2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) European Heart J 2016; published online before print May 20, 2016 doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehw128

Share this post: