Share this post:

The following is Part 2 of a 2-part series. Part 1 is Flipping Your Rotation (Part 1 of 2): The Fundamentals.

At this point, you may be wondering how the flipped classroom could benefit you since rotations are already made up of mostly active learning. But do you often find it challenging to find time for students given all of your other job responsibilities? And, when you do find time for teaching, are you often inundated with requests for drug or disease state reviews (e.g., “bugs and drugs”, “vasopressors”) rather than applying the topics that students should have already learned in the classroom? If you answered “yes” to either of these questions, then flipped learning may be the solution for you!

Preparing for Effective Instruction

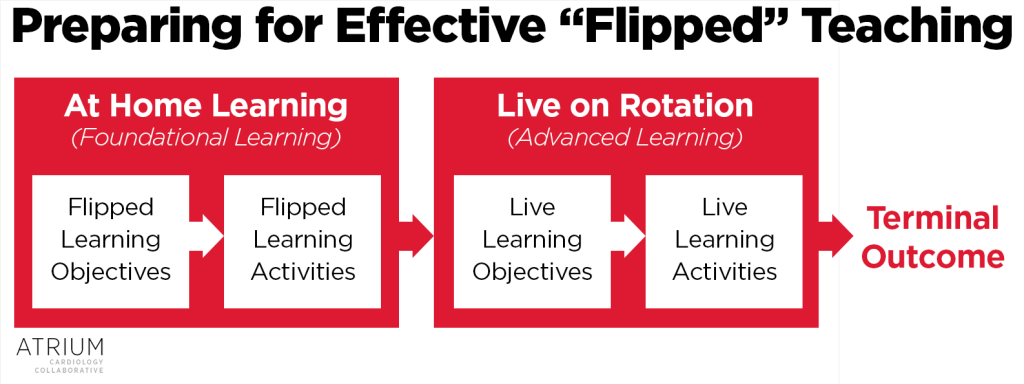

One mistake that instructors sometimes make when implementing flipped learning is failing to provide direction on how flipped content relates to students’ learning. Flipping your rotation won’t work as well if you post videos but expect students to figure out everything on their own! As with other types of instruction, it is important to integrate the basics of instructional design (including learning objectives and activities) into both flipped and live instruction, as shown in the figure below:

Incentivizing Preparation

Although we often wish that the joy of learning would be enough to incentivize preparation, we recognize that many learners will require other incentives to prepare for a live session. This is easy in the classroom, where you can utilize in-class assignments or quizzes. Unfortunately, rotation evaluations rarely provide this degree of flexibility. One way to overcome this is to use the “entrance ticket” concept, where you require learners to perform foundational work before they can participate in an advanced session. Examples of entrance ticket-type assignments include cases or practice problems assigned as homework, student-submitted questions to guide the topic discussion, and self-reflection exercises submitted ahead of time.

Snapshot Assessments

Another benefit of the activities mentioned above is that you can use these to obtain a snapshot assessment of learner comprehension. This allows you to tailor your instruction and fill in gaps before moving onto more advanced concepts. Rather than having your entire discussion mapped out ahead of time, allow yourself some time at the beginning of the live learning session (or before each major concept) to perform these assessments and any necessary “catch up” teaching. Allowing for this flexibility may take some getting used to at first (especially for new preceptors), but learners really appreciate this format because of the individualization it provides.

Repurposing Your Live Session

Now that learners have been exposed to the content ahead of time, the next step is to repurpose your live sessions so that you can focus on higher-order concepts. We have found that preceptors rarely have a problem at this stage because this is what they’ve wanted to all along – they’ve just previously not had the time to do it, or the students weren’t prepared for it!

Putting it All Together

Now that we have covered the basics of flipped learning on rotations, let’s put it all together in an example. Let’s say we would like a student to be able to design an antihypertensive regimen for an individual patient (the Terminal Outcome). Advanced Objectives for this outcome might include concepts like “Identify compelling conditions” or “Select the appropriate dose and route of administration based on the severity of hypertension.” As for most preceptors, our Advanced Activity would probably be for the student to prepare and present a patient case. Before we have the student do this for an actual patient, there are some important foundational concepts that he or she should know (Flipped Learning Objectives), such as “Classify the severity of hypertension based on patient presentation.” To help the student achieve this objective, we could assign them a short screencast like the one below:

To gain a snapshot assessment of their learning prior to the patient discussion, we might try a quick multiple choice question to ensure there are not any gaps in their learning. For example:

Which of the following scenarios would be considered a hypertensive emergency?

- 34 year old woman with a BP of 226/142 mmHg presenting with a ST-segment elevation MI

- 58 year old man with a blood pressure (BP) of 180/122 mmHg with end-stage renal disease and history of transient ischemic attacks presenting for a routine check-up

- 69 year old woman with a BP of 220/160 mmHg presenting with a community acquired pneumonia

- 72 year old man with a BP of 196/154 mmHg with a history of recurrent strokes presenting for a colonoscopy

If the student passes the assessment (Answer A), we can move on into higher-order learning activities. If not, we may need to spend some time filling in gaps in their learning before transitioning to more advanced concepts.

Conclusion

We hope you enjoyed this overview of integrating the flipped classroom into your rotation. We have found it allows us to focus on more advanced topics with our learners while also allowing us to tailor the experience to their progress. If you would like to share your experiences with us, we’d love to hear from you! Also feel free to email us at ATRIUM@rx.umaryland.edu if you have any questions.

|

Brent N. Reed, PharmD, BCPS-AQ Cardiology, FAHADr. Reed is an assistant professor in the Department of Pharmacy Practice and Science at the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy, and practices as a clinical pharmacy specialist in advanced heart failure at the University of Maryland Medical Center in Baltimore, MD. Follow him on Twitter @brentnreed |

Share this post: