Share this post:

Authors: Stormi Gale, PharmD, BCCP

Despite the known role of inflammation in atherosclerosis, interventions beyond statins that address this mechanism have been plagued with extreme costs and/or intolerable side effects.1,2 As a relatively low-cost and acceptably-tolerated medication, colchicine would be a practical choice to target the inflammatory nature of atherosclerosis. The promise of this therapy was furthered with the publication of the Low-Dose Colchicine (LoDoCo) trial, in which colchicine was associated with a reduction in composite acute coronary syndrome, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, or noncardioembolic ischemic stroke (HR, 0.33; 95% CI, 0.18 to 0.59; p<0.001).3

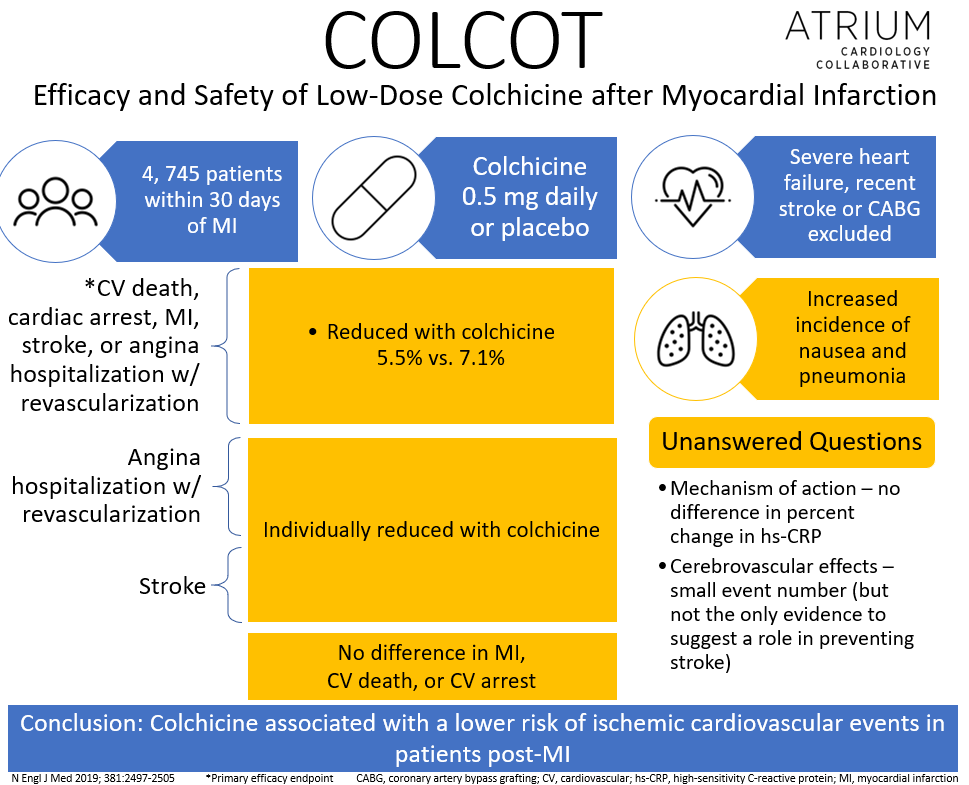

The Colchicine Cardiovascular Outcomes Trial (COLCOT) randomized 4,745 patients within 30 days of myocardial infarction (MI) to either colchicine 0.5 mg daily or placebo.4 Patients with severe heart failure, EF < 35%, recent stroke or coronary artery bypass grafting were excluded. Over 90% of patients enrolled received percutaneous coronary intervention for their index event. Unsurprisingly, most patients were also on dual antiplatelet therapy, a statin, and a beta-blocker at enrollment. After a median follow-up of almost 2 years, colchicine reduced the composite primary efficacy endpoint of death from cardiovascular causes, resuscitated cardiac arrest, myocardial infarction, stroke, or urgent hospitalization for angina leading to coronary revascularization (5.5% vs. 7.1%; HR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.61 to 0.96; P=0.02). However, this was driven primarily by the reduction in stroke (HR, 0.26; 95% CI, 0.10 to 0.70) and hospitalizations for angina leading to revascularization (HR, 0.50; 95% CI, 0.31 to 0.81), with no difference in any other component of the primary composite endpoint. There was no difference in adverse events other than an increased incidence of nausea and pneumonia with colchicine.

Initially, one might suspect that the benefits of colchicine post-MI might be related to reductions in the risk of pericarditis. However, the authors dispute this claim as the mean enrollment of 13.5 days post-MI is outside the window in which patients are at highest risk for the occurrence of pericarditis.

Despite appearing like a positive study at first glance, skepticism regarding the role of colchicine in reducing ischemic events has followed the publication of COLCOT. A high dropout rate may have affected both the safety and efficacy outcomes. Additionally, many doubt the results are due to anti-inflammatory mechanisms, citing that there was no difference in the percent change in markers of inflammation, including high-sensitivity C-reactive protein level at 6 months. Furthermore, small event numbers question whether the reduction in stroke is a direct result of colchicine or due to chance alone. However, previous meta-analyses have also demonstrated a protective benefit in both primary and secondary cerebrovascular events.5

Similarly, critics of this study question the value of reductions in individual components of a composite outcome (stroke and coronary revascularization) without an effect on arguably more important outcomes such as cardiovascular death. Although the results of COLCOT may not be as overwhelmingly beneficial as other recent trials, is a reduction in nonfatal events and revascularization not a meaningful endpoint? What if this same bar had been applied to clopidogrel in CURE?6

Bottom Line

Whether colchicine gets integrated into guidelines for the management of patients post-MI remains to be seen. However, given the lower-cost (although still prohibitive for some) and limited side effect profile of colchicine, its use in this population is certainly reasonable. It may be particularly preferred in those who require therapies to reduce the incidence of gout or in those with recurrent anginal symptoms. Nonetheless, as individualized care becomes increasingly important, we must ensure that patients’ goals are prioritized, including whether a reduction in nonfatal events is worth the added cost and risk for adverse effects. Discussions surrounding the benefits and risks of colchicine therapy in this setting are necessary as we encourage patients to play an important role in their care.

|

Stormi Gale, PharmD, BCCP

|

References:

- Ridker PM, Everett BM, Thuren T, et al. Antiinflammatory Therapy with Canakinumab for Atherosclerotic Disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(12):1119-1131.

- Ridker PM, Everett BM, Pradhan A, et al. Low-Dose Methotrexate for the Prevention of Atherosclerotic Events. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(8):752-762.

- Nidorf SM, Eikelboom JW, Budgeon CA, Thompson PL. Low-Dose Colchicine for Secondary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(4):404-410.

- Tardif J-C, Kouz S, Waters DD, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Low-Dose Colchicine after Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(26):2497-2505.

- Khandkar C, Vaidya K, Patel S. Colchicine for Stroke Prevention: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Ther. 2019;41(3):582-590.e3.

- The Clopidogrel in Unstable Angina to Prevent Recurrent Events Trial Investigators. Effects of Clopidogrel in Addition to Aspirin in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes without ST-Segment Elevation. N Engl J Med. 2016; 345:494-502

Share this post: