Share this post:

Author: Sandeep Devabhakthuni, PharmD, BCCP

Since the 2017 American College of Cardiology (ACC) Expert Consensus Decision Pathway (ECDP) for Optimization of Heart Failure Treatment was published, new evidence for novel therapies for HFrEF has demonstrated overwhelmingly positive clinical outcomes.1 In particular, angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors (ARNIs) and sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors have garnered significant attention.2-5 Thus, the 2021 Update to the 2017 ACC ECDP has been published to incorporate these emerging therapies while we await the comprehensive and definitive heart failure (HF) guideline currently under development.6 Here are four key takeways from the 2021 Update to the 2017 ACC ECDP:

1. Never delay GDMT.

Not surprisingly, the 2021 Update focuses heavily on optimization of guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT), since the reported number of patients receiving the indicated agents and/or the target doses is dismal.6 Less than 25% of patients with HFrEF, without contraindications, are prescribed all GDMT, with only 1% receiving target doses of an ACEI/ARB/ARNI, beta blocker, and an aldosterone antagonist.7 The ideal time to optimize GDMT is during hospitalization for management of acute HF.8 In the outpatient setting, adjustment of therapies should be considered every 2 weeks to achieve target/maximal tolerated doses within 3-6 months of initial diagnosis. An echocardiogram should be repeated 3-6 months in patients with non-ischemic cardiomyopathy after achieving target doses of GDMT to determine if an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator/cardiac resynchronization therapy should be recommended to the patient.6

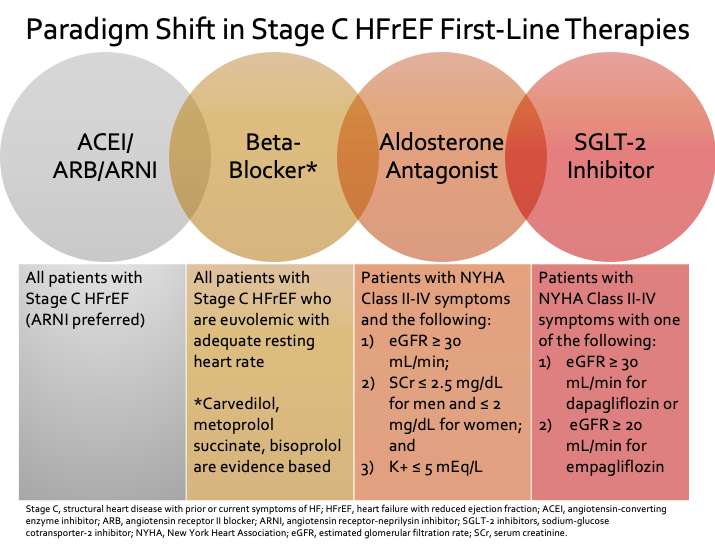

2. The new backbone of GDMT should include a beta blocker, ACEI/ARB/ARNI, aldosterone antagonist, and SGLT-2 inhibitor.

For patients with newly diagnosed American Heart Association (AHA) Stage C HFrEF (structural heart disease with prior or current symptoms of HF), a beta blocker and an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI)/angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB)/ARNI should be started in any order.6 Each agent should be up-titrated to maximally tolerated or target dose. Initiation of a beta-blocker is better tolerated when patients are euvolemic with an adequate resting heart rate.Only evidence-based beta-blockers (bisoprolol, carvedilol, or metoprolol succinate) should be used in patients with HFrEF.1,6

Renin-angiotensin inhibitors can be initiated at any time. Due to new evidence, ARNI therapy is now preferred first-line over an ACEI or ARB, even those who are naïve to one of these agents. Use of sacubitril/valsartan can be initiated in most patients without hypotension or very advanced HF.2,3,9-11

“I was glad to see ARNI therapy preferred over ACEI and ARB for our patients with stage C HFrEF in this ECDP. There will definitely be patients for whom ARNI initiation will not be possible. However, my hope is that this recommendation will lead pharmacy payers to update their formulary, allowing easier and more affordable access to ARNI therapy. Unfortunately, there are currently many hoops to jump through to get ARNI for qualifying patients.”

Dr. Stormi Gale, Applied Therapeutics, Research, and Instruction at the University of Maryland (ATRIUM) Cardiology Collaborative faculty member who specializes in advanced heart failure

Renal function and potassium should be checked within 1-2 weeks of initiation or dose up-titration of an ACEI/ARB/ARNI. Hyperkalemia and/or abnormal renal function are common barriers to achieving target medication doses with these agents and/or aldosterone antagonists.12 Patients with, or at risk for, hyperkalemia should be educated on a low potassium diet. Novel potassium binders (e.g., patiromer) may be considered when hyperkalemia precludes use or dose titration.6,13,14

Addition of aldosterone antagonist should be considered in patients with New York Heart Association (NYHA) class II-IV symptoms with close monitoring of electrolytes.6 A sodium-glucose-lowering-tranport (SGLT)-2 inhibitor should be considered for HFrEF with NYHA class II-IV patients unless patient has advanced kidney disease (estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] < 30 mL/min for dapagliflozin or eGFR < 20 mL/min for empagliflozin) or type 1 diabetes mellitus.4-6 For Black patients who have persistentYHA class III-IV symptoms despite being optimized on ARNI/beta-blocker/aldosterone antagonist/SGLT-2 inhibitor, hydralazine and isosorbide dinitrate is recommended to potentially further decrease mortality.6 The 2021 Update was published prior to the Food and Drug Administration approval of vericiguat in January 2021; potential role in HFrEF management and limitations have been discussed in a previous blog.

3. Medication adherence needs to be assessed at every patient encounter.

We would be remiss, as pharmacists, if we did not highlight this concept. Regular assessment of medication adherence is crucial. Interventions that can improve adherence should be personalized to the particular demands for each patient, including patient education, medication taking reminders, and incentives to promote adherence.15

4. Discuss goals of care with HFrEF patients early and reassess periodically.

Goals of care should be addressed during the course of illness with HFrEF, and expectations should be reviewed to guide timely decisions. The 2021 Update recommends the use of decision support tools when feasible.6,16-19 End-of-life care in HFrEF includes reassessment of GDMT if not tolerated, and palliative care consultation can assist with noncardiac symptoms.

“It would be amazing if every patient with HFrEF could be enrolled in palliative care, especially as their disease progresses. However, as this ECDP states, there unfortunately are not enough palliative care providers for those with HFrEF who would benefit from their care nor do all people have access to one, even if they wanted. I think that my favorite line in the document was “Soliciting goals of care and focusing on quality of life are appropriate throughout the clinical course of HF and become increasingly important as the disease progresses.”

Dr. Kristin Watson, ATRIUM Cardiology Collaborative faculty member specializing in ambulatory heart failure care

Establishing these goals is a great way, in my opinion, to form a trusting relationship with the person for whom you are providing care. It also serves as a reminder that we are taking care of people and that care is not one-size fits all. Goal setting can help us navigate developing a treatment plan with the patient and recognizing that sometimes, it is okay to say “enough is enough”. REMAP (Reframe, Expect emotion, Map out patient goals, Align with goals, Propose a plan) can be a helpful tool to apply.Do not forget that goals of care need to be re-evaluated periodically as these will likely change for the patient and their loved ones over time. Here are some great resources to learn more about establishing goals of care:16-19

- Childers JW, Back AL, Tulsky JA, Arnold RM. REMAP: A Framework for Goals of Care Conversations. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13(10):e844-e850.

- VITALtalk. Address Goals of Care: smoothing discussions about prognosis and treatment.

- VITALtalk. Transitions/Goals of Care: Addressing Goals of Care: Using the REMAP tool.

- Allen LA, Stevenson LW, Grady KL, et al. Decision making in advanced heart failure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(15):1928-1952.”

Bottom Line

The 2021 Update to the 2017 ACC ECDP provides a revised framework for making decisions in caring for a patient with HFrEF. This update provides guidance on how to initiate and optimize GDMT including emerging therapies that have recently demonstrated excellent clinical outcomes. The first-line therapies that should be considered for all patients include an evidence-based beta blocker, ACEI/ARB/ARNI (ARNI preferred), aldosterone antagonist, and SGLT-2 inhibitor. For persistently symptomatic Black patients already optimized on these medications, hydralazine-isosorbide dinitrate combination should be considered to potentially further reduce mortality. The 2021 Update also provides clinicians guidance on how to optimize medication adherence and initiate goals of care discussions with HFrEF patients.

Acknowledgments: Dr. Kristin Watson, PharmD, BCCP and Dr. Stormi Gale, PharmD, BCCP

|

Sandeep Devabhakthuni, PharmD, BCCP

|

Reviewed by: Kristin Watson, PharmD, BCCCP

References:

- Yancy CW, Januzzi Jr JL, Allen LA, et al. 2017 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway for Optimization of Heart Failure Treatment: answers to 10 pivotal issues about heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Task Force on Expert Consensus Decision Pathways. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:201-230.

- McMurray JJV, Packer M, Desai AS, et al. Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:993-1004.

- Velazquez EJ, Morrow DA, DeVore AD, et al. Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition in acute decompensted heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:539-548.

- McMurray JJV. Solomon SD, Inzucchi SE, et al. Dapagliflozin in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1995-2008.

- Packer M, Anker SD, Butler J, et al. Cardiovascular and renal outcomes with empagliflozin in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1413-1424.

- Maddox TM, Januzzi Jr JL, Allen LA, et al. 2021 update to the 2017 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway for Optimization of Heart Failure Treatment: answers to 10 pivotal issues about heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021:S0735-1097.

- Greene SJ, Butler J, Albert NM, et al. Medical therapy for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: the CHAMP-HF registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018:351-366.

- Hollenberg SM, Warner Stevenson L, Ahmad T, et al. 2019 ACC expert consensus decision pathway on risk assessment, management, and clinical trajectory of patients hospitalized with heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74:1966-2011.

- Januzzi JL Jr., Prescott MF, Butler J, et al. Association of change in N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide following initiation of sacubitril-valsartan treatment with cardiac structure and function in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. JAMA. 2019;322:1-11.

- Senni M, McMurray JJV, Wachter R, et al. Impact of systolic blood pressure on the safety and tolerability of initiating and up-titrating sacubitril/valsartan in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction: insights from the TITRATION study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2018;20:491-500.

- Khariton Y, Fonarow GC, Arnold SV, et al. Association between sacubitril/valsartan initiation and health status outcomes in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol HF. 2019;7:933-941.

- Juurlink DN, Mamdani MM, Lee DS, et al. Rates of hyperkalemia after publication of the Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:353-51.

- Bakris GL, Pitt B, Weir MR, et al. Effect of patiromer on serum potassium level in patients with hyperkalemia and diabetic kidney disease: the AMETHYST-DN randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314:151-61.

- Kosiborod M, Rasmussen HS, Lavin P, et al. Effect of sodium zirconium cyclosilicate on potassium lowering for 28 days among outpatients with hyperkalemia: the HARMONIZE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312:2223-2233.

- Kini V, Ho PM. Interventions to improve medication adherence: a review. JAMA. 2018;320:2461-2473.

- Childers JW, Back AL, Tulsky JA, Arnold RM. REMAP: A Framework for Goals of Care Conversations. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13(10):e844-e850.

- Address Goals of Care: smoothing discussions about prognosis and treatment. https://www.vitaltalk.org/topics/reset-goals-of-care/. Accessed 21 January 2021.

- Transitions/Goals of Care: Addressing Goals of Care: Using the REMAP tool. https://www.vitaltalk.org/guides/transitionsgoals-of-care/. Accessed 21 January 2021.

- Allen LA, Stevenson LW, Grady KL, et al. Decision making in advanced heart failure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(15):1928-1952.

Share this post: